Asian NATO proposal should remain a dream

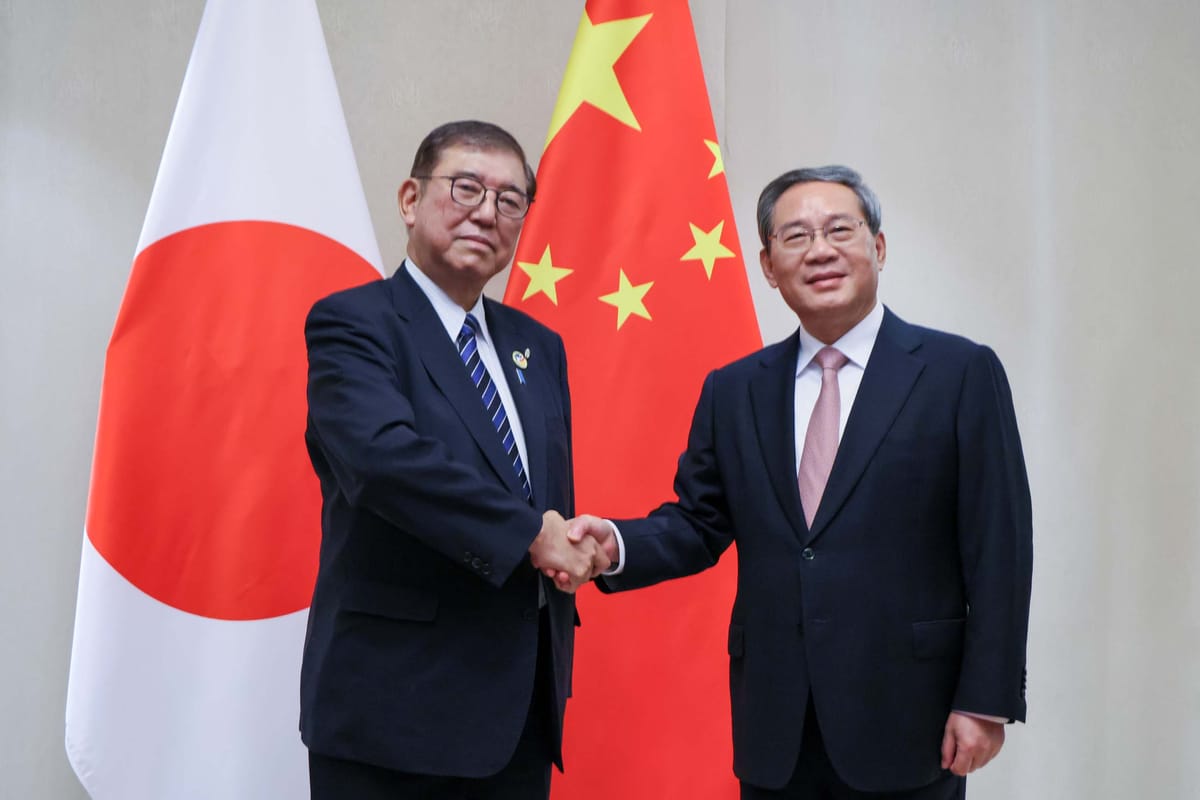

Amid growing concerns over tensions in the South China Sea and Taiwan, Japan’s new Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba proposed creating a NATO-like alliance in Asia to counter Chinese expansion and aggression. The Asian NATO would include binding, collective defense measures such as NATO’s Article 5, which mandates that an attack on one will be an attack on all. This proposal is just one layer of Ishiba’s aggressive anti-China foreign policy. The U.S. now faces a key decision: whether to support this alliance or to pursue more alternate strategies in the Indo-Pacific. To maintain stability in the region, the U.S. must focus on strengthening small partnerships and reject the idea of an Asian NATO.

Currently, U.S. policy in the Indo-Pacific involves bilateral alliances with Japan, South Korea, the Philippines and Australia. These security alliances revolve around the idea that bilateral collaboration will deter Chinese attacks. Additionally, the United States participates in the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, a diplomatic partnership that includes the United States, Australia, India and Japan. The Quad serves to facilitate communication between countries located near the Indian and Pacific Ocean. Historically, America has avoided formalizing a NATO-like alliance in Asia, instead opting for more flexible partnerships with individual countries. According to the United States Agency for International Development, the U.S. supports a “free and open Indo-Pacific” and provides humanitarian, economic and security support to select allies. Unlike NATO, these partnerships allow the U.S. to adapt quickly to global affairs because they do not include binding mandates such as NATO’s Article 5.

If successful, the alliance could create greater stability in Asia by deterring conflict in contested areas like Taiwan and the South China Sea. However, if it fails at its goals to unify key players or alienates economically interdependent countries, it runs the risk of undermining regional stability and forcing weaker nations closer to China’s orbit. Here’s a breakdown at how this initiative might affect different sectors in the region:

Japan: As the proposal’s architect, Japan views the alliance as a necessary measure to ensure its security from China and reinforce ties with the U.S., especially if nuclear-sharing arrangements come into play. It’s important to note that the Liberal Democratic Party, a pro-Chinese political group, in Japan lost their long-time majority in recent elections. Instead, Ishiba will work with a coalition government, which will include members who are both for and against China. Japan’s leadership under Ishiba is actively pursuing this alliance to maintain stability and reduce reliance on solely bilateral security agreements with the U.S.

South Korea and the Philippines: Both countries stand to gain strategically from U.S. protection by reducing their reliance on China, though they also stand to lose economically if they join an Asian NATO due to their dependence on China. According to the Peterson Institute for International Economics, since 2017, South Korea’s exports to China have been larger than that of the United States and Japan combined. However, last year, South Korea’s exports to the United States and Japan combined overtook that of China for the first time since 2006. Furthermore, Vincente Rafael, a history professor at the University of Washington, said “The Philippines is economically dependent on its trade relations with the United States.” This partnership is also why, 30 years after the Phillipines moved to end permanent U.S. military presence, the country gave the U.S. access to four new military bases last year to deter Chinese aggression in the South China Sea.

India: According to Reuters, India has explicitly rejected the possibility of joining Asian NATO, citing its commitment to independent foreign policy. When speaking at the U.N. regarding the prospect of an Asian NATO, Indian Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar said “We have ... a different history and different way of approaching.” India’s rejection weakens the cohesiveness and strength of the Asian NATO by removing a major military and political force from the equation.

Southeast Asia: Southeast Asian countries have responded differently to Chinese aggression and expansion. Vietnam has outwardly rejected Chinese investment over national security concerns. In August of 2024 for example, Vietnam sped up efforts to expand islands and reclaim land in the South China Sea, according to the Washington Post. However, countries such as Thailand and Cambodia are economically dependent on China. According to the Lowy Institute, their “hands are tied.”

China: China vehemently opposes an Asian NATO, viewing it as a direct threat. After the proposal was announced, China warned Japan to be “cautious in its words and deeds” and said the Asian NATO “hyped up the non-existent ‘China threat.’” This alliance could further escalate Sino-American tensions.

United States: After Ishiba’s proposal, Daniel Kritenbrink, the U.S. assistant secretary of state for East Asia and the Pacific dismissed the proposal, saying it was too early to discuss the idea.

The proposal will likely escalate tensions with China and force Asian countries to choose between pleasing China to protect their economies or siding with the United States for security. Instead, the United States can focus its attention on creating and strengthening existing smaller, multilateral security alliances that emphasize collective security without formalizing strict alliance obligations. These alliances increase security cooperation between countries in Asia without outwardly threatening China’s claims. For example, these multilateral security alliances could look like the American–Japanese–Korean trilateral pact (JAROKUS), which serves as a security pact between Japan, South Korea and the United States. Through this agreement, the US is able to coordinate military responses with its partners in Asia while minimizing the risk of Chinese retaliation.

Those who support an Asian NATO argue that a strong alliance would serve as the most powerful deterrent against China. They also argue that only a mandated security agreement would deter China, as discussions or more flexible commitments seem too weak. However, an Asian NATO at this stage would be more likely to split alliances than strengthen them, by forcing countries to pick a side.

In choosing a response, U.S. policymakers must balance deterrence with de-escalation. An Asian NATO presents multiple challenges that would undermine regional unity instead of strengthening it. By employing more flexible, smaller multilateral partnerships over rigid and broad alliances, the U.S. can support regional allies while minimizing the risk of conflict. Thus, through these multilateral partnerships, the US can simultaneously support stability in Asia and retain its flexibility. In a region as unstable as Asia, tides could turn with a single decision. Thus, the U.S. must prioritize its adaptability in the Indo-Pacific.